Uccellacci e Uccellini. Da Darwin a Pasolini

di Silvia Bonomini

«I suoni emessi dagli uccelli offrono, per parecchi aspetti, l’analogia più vicina al linguaggio, perché tutti gli individui della stessa specie emettono grida istintive che esprimono le loro emozioni; e tutte le specie che cantano esercitano la loro facoltà istintivamente» Charles Darwin

Uccellacci e Uccellini. Da Darwin a Pasolini è il titolo della mostra dedicata ad Alice Zanin nello spazio espositivo dell’Assemblea Legislativa della Regione Emilia Romagna: oltre trenta sculture di uccelli di varie specie raccontano allegorie fiabesche e invitano alla riflessione sugli svariati significati attribuiti, nel corso dei secoli, alle meraviglie dell’ornitologia. Il titolo fa riferimento all’omonimo capolavoro cinematografico realizzato nel 1966 dal grande regista, a cui Bologna ha dato i natali, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Uccellacci e Uccelliniè un film diventato icona italiana ed interpretato da Totò e Ninetto Davoli. E’ proprio dalla visione di questo film – intriso di metafore, messaggi politici e sociali – che la Zanin passa dalla Natura alla Cultura e realizza una trasposizione visiva che percorre un ampio spettro di interessi, spaziando dalla scienza alla storia, dal mito alla religione, dal costume alla dimensione artistica. Se il film è una parabola moderna che dal Vangelo prende i temi fondamentali che riguardano i rapporti fra gli uomini e li sviluppa in una società dove i rapporti di classe sono conflittuali, le sculture di Alice Zanin indagano aspetti religiosi e mitologici che evidenziano un mondo, quello dell’ornitologia, fatto di “oppressi ed oppressori”.

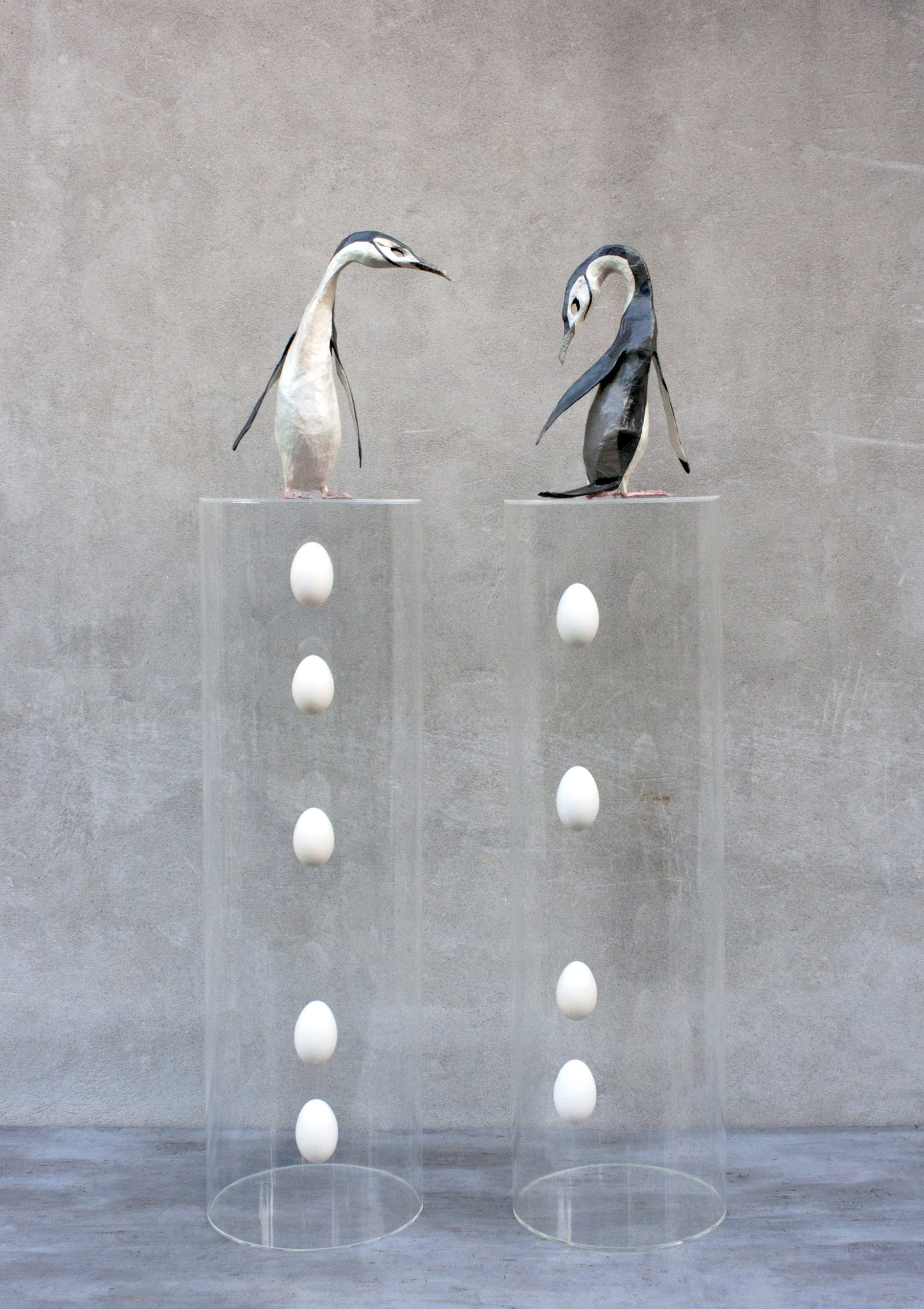

In Post Fata Resurgam è evidente l’allusione alla leggenda della fenice, mitico uccello sacro agli antichi egizi che, dopo la morte, rinasce dalle proprie ceneri e che, quindi, simboleggia la resilienza. E resilienti sono Totò e Fra Ninetto per la loro tenacia a predicare – come San Francesco ne Il cantico delle creature – pace e amore prima ai falchi e poi ai passerotti. In molte opere esposte è presente il simbolismo religioso: le jacane crestate, protagoniste dell’opera Si deus pro nobis, quis contra nos,sono anche chiamate “uccelli di Cristo” per la loro capacità di appoggiarsi delicatamente sull’acqua dando l’impressione di camminarvi in superficie. In Love at second eggle uova assumono un doppio significato: se da un lato simboleggiano la vita eterna dopo la resurrezione, accostate ai pinguini crestati evocano caratteristiche evolutive proprie del genere Eudyptesavvicinandosi al pensiero di Charles Darwin.

Tornando a Pasolini, dopo un primo successo nell’evangelizzare i volatili, Totò e Fra Ninetto – nel vedere un falco aggredire un passerotto – si rendono conto che falchi e passerotti saranno anche evangelizzati nell’amore, ma appartengono a classi sociali diverse, conflittuali, e fra loro è guerra eterna e morte reciproca. Questo, con grande delusione, frate Ciccillo dirà a San Francesco:

[…] noi i falchi l’avemo convinti, e mo’ i falchi come falchi l’adorano, er Signore; e pure li passeretti, l’avemo convinti, e pure ai passeretti, per conto loro, je sta bene, l’adorano, er Signore. Ma er fatto è che fra de loro… se sgrugnano…s’ammazzano, a frate Francè… Che ce posso fa io se ce sta la classe dei falchi e la classe dei passeretti, che nun ponno annà d’accordo fra de loro?

San Francesco inciterà a proseguire l’evangelizzazione:

[…] Che ce puoi fa? Ma tutto ce puoi fa, co’ l’aiuto del Signore! […] dovete insegnà ai falchi e ai passeretti tutto quello che nun hanno capito […]. Coraggio, fratelli. Dovete ricomincià tutto daccapo…

Seppur intriso di messaggi politici, sociali e religiosi si nota come il film presenti un chiaro registro ideo – comico che viene sottolineato dal coro di uccelli. Una parabola ripresa con note ironiche dalla Zanin in Waterloo riferendosi all’omonima battaglia che vide la sconfitta napoleonica nella quale gli “oppressi” sono rappresentati da uccelli pigliamosche reali amazzoniani (Onychorhynchus coronatus) a ricordare il fiero portamento e il cappello napoleonico nero, rosso e giallo. E’ un chiaro riferimento all’ornitomanzia, l’antica pratica greca di leggere auspici nel comportamento degli uccelli. E’ chiaro che, come nel film di Pasolini, anche nelle sculture della Zanin, si uniscono elementi sacri e profani in una sorta di divinazione fondata sull’osservazione del volo e del canto degli uccelli. In Uccellacci e Uccellini Totò e Ninetto riusciranno – dopo averli osservati in volo – a comunicare con i passeri saltellando: <<tic, tic, tic, tac, tac…>> è il motivo che traduce il linguaggio dei piccoli volatili. Così la Zanin riproduce in volo la gru coronata (balearica regulorum) in Verba volant scripta desiliunte la civetta (Athene noctua) in Verbavolant scripta lucubrant, richiamando l’arte mantica dell’interpretazione dei segni naturali e accostando “uccellacci” ad “uccellini”.

Da sempre, quindi, metafora della condizione umana, gli uccelli sono animali che sono stati spesso utilizzati nelle più svariate arti visive e non. In pittura, ad esempio, è famoso l’episodio che rappresenta La predica degli uccelli dipinta da Giotto sulla controfacciata della Basilica Superiore di Assisi; in letteratura non si può non citare la Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri, ricca di figure allegoriche, metafore e similitudini che richiamano il mondo degli uccelli.

Nel grande cinema, ad anticipare di qualche anno Pasolini nell’utilizzare il mondo dei volatili, è The birds di Alfred Hitchcock, un classico che mette in evidenza come gli «uccelli» siano una minaccia costante sopra il destino dell’uomo: essa può annidarsi ovunque, e tanto più è terribile quanto più è nascosta fra le pieghe della vita quotidiana, fra le cose, gli ambienti e gli esseri (umani e non) che più ci rassicurano.

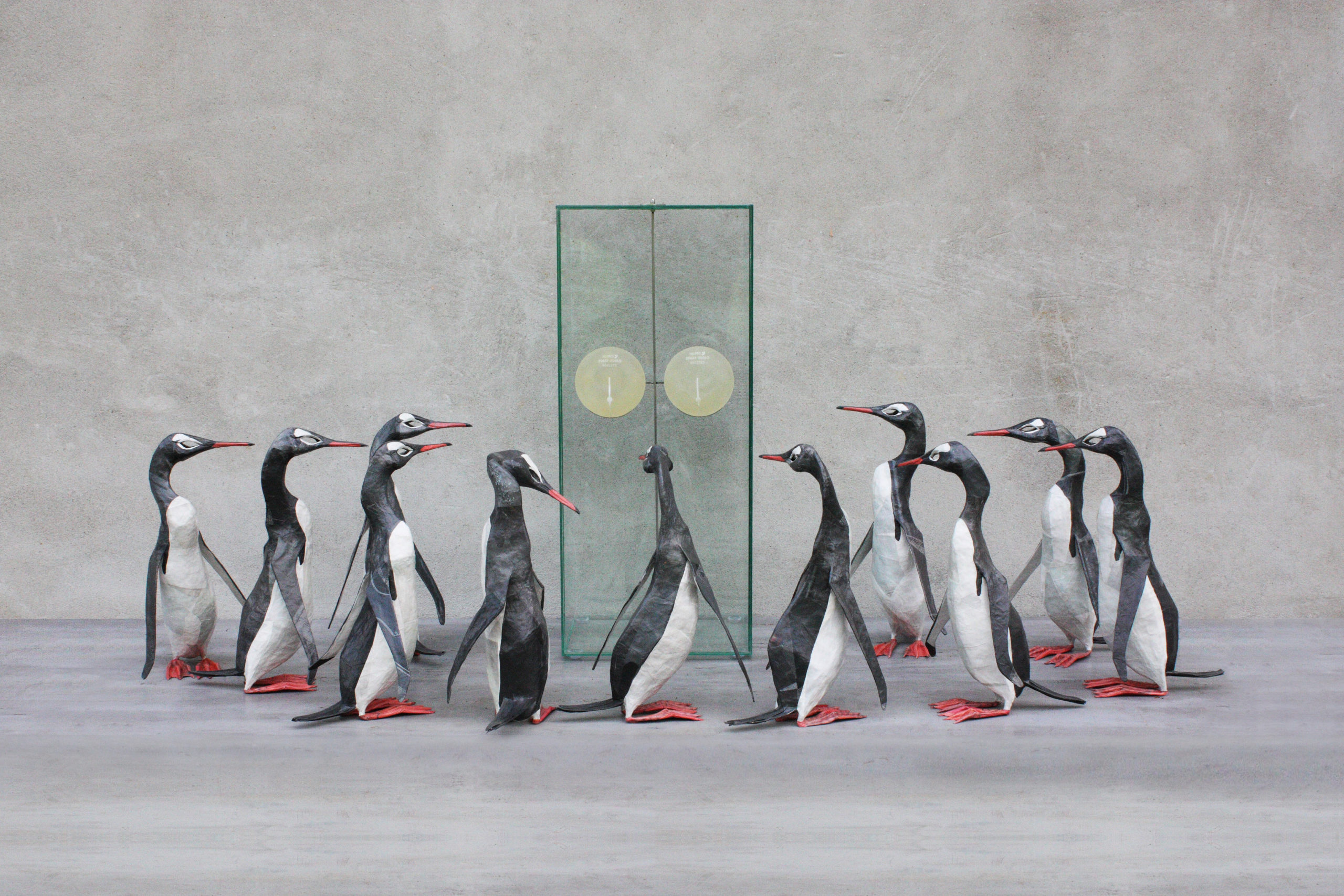

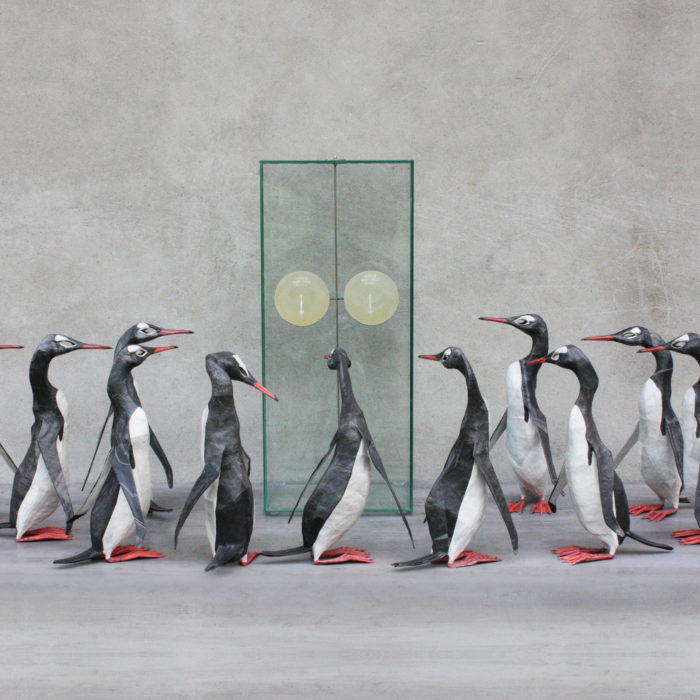

E’ grazie ad una approfondita conoscenza culturale che le sculture di Alice Zanin diventano icone di favole contemporanee. Il suo sembra un linguaggio immediato ma, in realtà, utilizza una grammatica espressiva adeguata non solo a far riflettere sulle condizioni umane, ma anche sulle urgenze della contemporaneità. Penguin colony takes implants for ice packs è un’installazione di dieci pinguini (Pygoscelis papua) che racchiude diverse chiavi di lettura vicine all’idea di scultura sociale elaborata da Joseph Beuys, intesa come processo in continuo divenire dei legami ecologici, politici, economici, storici e culturali che costituiscono l’apparato sociale con l’intento di salvare il pianeta. Nell’installazione della Zanin è, infatti, immediato il riferimento a temi ecologisti quali il surriscaldamento globale e il conseguente scioglimento dei ghiacciai nella schiera dei pinguini assiepati attorno alla teca, assorti nella contemplazione di un sacrale Antartide miniaturizzato. Ad arricchire iconograficamente l’installazione vi sono protesi in silicone che testimoniano, in modo sarcastico oltre che ironico, una società dove essenziale appare la frivolezza estetica: un modo per criticare l’era del consumismo.

Così la Zanin riprende meticolosamente le peculiarità morfologiche dei pigoscelidi di Papua ed evidenzia la striscia rosso acceso nella sezione centrale del becco e le “virgolette” bianche sopra agli occhi che ricordano un ammiccante maquillagedi rossetti e di ombretti. Qui è presente la fusione dello spettacolo e dell’arte proprio come nel film Uccellacci e Uccellini dove, utilizzando le parole di Alfredo Bini – produttore di Pier Paolo Pasolini – viene messa «in evidenza una realtà visiva e comica e spettacolare con un valore immediato: anche se qualcuno potrà non comprendere del tutto i significati, tuttavia l’impressione immediata sarà valida e fruttifera, anche in senso ideologico».

Come nel capolavoro cinematografico di Pasolini, anche in tutta l’opera di Alice Zanin vi è una forte connotazione simbolicache – tuttavia – si unisce ad un vivace interesse scientifico trovato grazie alla lettura degli scritti di Charles Darwin, fondatore della teoria dell’evoluzione delle specie animali. Infatti, in alcuni passi del libro L’Origine dell’Uomo e della Selezione Sessuale, Darwin definisce gli uccelli come «i più dotati di senso estetico tra tutti gli animali» e posseggono il nostro stesso gusto del bello. Così, partendo dall’idea che in molte specie di volatili si possono ritrovare forme d’arte, Alice Zanin ha saputo unire capacità tecniche e conoscenze scientifiche, oltre che morfologiche, ottenendo eleganti sculture arricchite da significativi rimandi culturali. Gli ibis scarlatti (Eudocimus ruber) sono degli uccelli che vivono in America centrale e sono i protagonisti dell’installazione intitolata Rouages in quanto assume il significato autonomo di “ingranaggi” ma, al tempo stesso, è una fusione delle parole rouge (rosso) e nouages(nuvole). Per realizzare questa installazione la Zanin ha preso spunto dal testo darwiniano L’espressione delle emozioni nell’uomo e negli animali, pubblicato nel 1872, dove il naturalista definì il rossore come la più umana delle espressioni, in quanto l’unica provocata dall’attenzione sul sé in relazione alla società. Una profonda riflessione sul colore rosso, quella dell’artista piacentina, che può essere accostata alla teoria dei colori di Johann Wolfgang von Goethe che indica il porpora come “la più alta manifestazione del colore”, quella che racchiude in sé tutti gli altri, essendo il risultato dell’unione graduale degli estremi opposti giallo e blu. E se Uccellacci e Uccellini di Pier Paolo Pasolini ha contribuito ad indurre la Zanin a realizzare una serie di lavori esclusivamente dedicati agli uccelli, in Rouages non si possono certo escludere, echi ripresi da Deserto Rosso, capolavoro di un altro genio del cinema italiano: il ferrarese Michelangelo Antonioni.

Con le sue sculture Alice Zanin dona emozioni estatiche non solo grazie alla raffinatezza e alla precisione esecutiva, ma anche grazie all’attenta ricerca del potere evocativo delle immagini e alla ricchezza infinita e variegata di riferimenti culturali.

The Hawks and the Sparrows: From Darwin to Pasolini

by Silvia Bonomini

«The sounds uttered by birds offer in several respects the nearest analogy to language, for all the members of the same species utter the same instinctive cries expressive of their emotions; and all the kinds which sing, exert their power instinctively» Charles Darwin

The Hawks and the Sparrows: From Darwin to Pasoliniis the title of Alice Zanin’s exhibition, held in the exhibition space of the Legislative Assembly of the Emilia Romagna Region: over thirty sculptures of birds of various species tell fairy-tale allegories and invite to reflection on the many meanings attributed, over the centuries, to the wonders of ornithology. The title refers to the masterpiece of the same name made by the great director Pier Paolo Pasolini, to whom Bologna was the birthplace, in 1966. Interpreted by Totò and Ninetto Davoli, The Hawks and the Sparrowshas become an Italian icon. And it is from the very vision of this film – rich in metaphors, political and social messages – that Zanin moves from Nature to Culture, achieving a visual transposition that covers a wide range of interests, ranging from science to history, from myth to religion, from customs to the artistic dimension.While the film is a modern parable that draws from the Gospel the fundamental themes concerning relationships between men, developing them in a society where class relations are conflicting, Alice Zanin’s sculptures investigate religious and mythological aspects that highlight a world – that of ornithology – made up of “oppressed and oppressors”.

Post Fata Resurgamclearly allude to the legend of the phoenix, the mythical bird, sacred to the ancient Egyptians, that, once dead, reborn from its own ashes, symbolizing, therefore, resilience. And Totò and Brother Ninetto are resilient because of their tenacity in preaching peace and love – like Saint Francis in The Canticle of the Creatures–, first to the hawks and then to the sparrows. Religious symbolism is present in many of the works on display: the comb-crested jacanas, protagonists of Si deus pro nobis, quis contra nos, are also known as “birds of Christ” for their ability to gently lean on water, giving the impression of walking on its surface. In Love at second egg, eggs take on a double meaning: if on the one hand they symbolize the eternal life after resurrection, when combined with erect-crested penguins they evoke evolutionary characteristics that are typical of the eudyptesgenus, thus approaching the thought of Charles Darwin.

But going back to Pasolini: after a first success in evangelizing the birds, Totò and Brother Ninetto, seeing a hawk attack a sparrow, realize that hawks and sparrows might be evangelized in love, but they still belong to different and conflicting social classes, and eternal war and mutual death divide them. This is what Friar Ciccillo will tell Saint Francis, with great frustration:

[…] Brother Francis, the hawks have been converted. The hawks, as hawks can, worship the Lord. And then, Brother Francis, we converted the sparrows. And the sparrows, too, as sparrows, also in agreement, worship the Lord. But between the two bunches they fight and kill each other! But what can I do, if the class of the hawks and of the sparrows can’t get along with each other?

But Saint Francis encourages them to continue the evangelization:

[…] You can do everything with the Lord’s help! […] That means you must go teach them what they haven’t understood […]. Come on, brothers. Go and begin again

Although imbued with political, social and religious messages, we can notice how the film presents a clear ideo-comic register, underlined by the chorus of birds. A parable that Zanin ironically revisits in Waterloo, referring to the battle that is well-known for Napoleon’s final defeat, in which the “oppressed” are represented by Amazonian royal flycatcher birds (Onychorhynchus coronatus), whose proud posture recalls the black, red and yellow Napoleonic hat. It is a clear reference to ornithomancy, the ancient Greek practice of reading auspices in the behaviour of birds. As in the film by Pasolini, it is clear that also in Zanin’s sculptures sacred and profane elements blend in a sort of divination based on the observation of the flight and song of birds. In The Hawks and the Sparrows, Totò and Ninetto will succeed – after having observed them in flight – to communicate with the sparrows by hopping: << tic, tic, tic, tac, tac … >> is the motif that translates the language of these small birds. Thus, Zanin reproduces the flight of the crowned crane (balearica regulorum) in Verba volant scripta desiliuntand of the owl (Athene noctua) in Verba volant scripta lucubrant, recalling the divination art of the interpretation of natural signs, juxtaposing “uccellacci” (large birds) to “uccellini” (small birds).

Since ever a metaphor of the human condition, birds are animals that have often been used in the most varied visual and non-visual arts. In painting, for example, well-known is the episode representing The sermon to the birdspainted by Giotto on the counter-façade of the Upper Church of Assisi; in literature, we cannot fail to mention the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, rich in allegorical figures, metaphors and similarities that recall the world of birds.

COLLECTION

In the history of cinema, anticipating of a few years Pasolini in the use of the world of birds, is The Birdsby Alfred Hitchcock, a classic that highlights how “birds” are a constant threat over man’s destiny. A threat that can lurk everywhere, and the more it is hidden between the folds of everyday life – between things, environments and beings (human and non) that most reassure us –, the more terrible it is.

Thanks to an in-depth cultural knowledge, Alice Zanin’s sculptures become icons of contemporary fables. Hers might look as an immediate language but, in reality, she uses an expressive grammar that is adequate not only to make people think about human conditions, but also about the urgencies of the contemporary world.Penguin colony takes implants for ice packs is an installation of ten penguins (Pygoscelis papua) that contains different interpretations that are close to the idea of social sculpture elaborated by Joseph Beuys, understood as a process in continuous evolution of the ecological, political, economic, historical, and cultural bonds that constitute the social apparatus, with the intent to save the planet. In the penguins gathered around the display case, absorbed in the contemplation of a sacral miniaturized Antarctica, Zanin’s installation is, indeed, an immediate reference to environmental issues such as global warming and the consequent melting of glaciers. To iconographically enrich the installation, silicone implants bear witness, in a sarcastic as well as ironic manner, to a society in which aesthetic frivolity is essential: a way to criticize the consumerism era.

Thus Zanin meticulously reproduces the morphological peculiarities of the long-tailed gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papua), highlighting the bright red stripe in the central section of their beaks and the white “quotation marks” above their eyes, which coquettishly recall a makeup made of lipsticks and eye shadows. Here is the fusion of entertainment and art, just like The Hawks and the Sparrowsmovie, where, in the words of Alfredo Bini – the producer of Pier Paolo Pasolini –, «A visual, comic and spectacular reality is highlighted with an immediate value: even if someone can not completely understand the meanings, however, the immediate effect will be valid and fruitful, even in an ideological sense».

As in the cinematographic masterpiece of Pasolini, throughout the work of Alice Zanin there is a strong symbolic connotation that combines with a lively scientific interest born from the reading of Charles Darwin writings, founder of the evolution theory of animal species. In fact, in some passages of the book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex,Darwin underlines how birds “appear to be the most aesthetic of all animals” and how they possess almost our same taste in beauty. Thus, starting from the idea that art forms can be found in many species of birds, Alice Zanin has been able to combine technical skills with scientific and morphological knowledge, obtaining her refined sculptures, enriched by substantial cultural references. Living in Central America, the scarlet ibises (Eudocimus ruber) are the protagonists of the installation entitled Rouages, a fusion of the words rouge(red) and nouages(clouds) that here also assumes the independent meaning of “gears”. In order to realize this installation, Zanin was inspired by the Darwinian text The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872, where the naturalist defines blushing as the most human of all expressions, as it is the only one caused by the attention on the self in relation to society. That of the artist from Piacenza is an in-depth reflection on the colour red, which can be compared to the colour theory of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who indicates crimson as “the highest manifestation of colour”, the one containing all the others, being the result of the gradual union of yellow and blue, two extreme opposite. And if Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Hawks and the Sparrowshas helped Zanin to carry out a series of works exclusively dedicated to birds, in Rouageswe cannot overlook echoes taken from Red Desert, a masterpiece of another genius of Italian cinema: Michelangelo Antonioni, from Ferrara.

With her sculptures, Alice Zanin gives ecstatic emotions, not only for the refinement and precision of execution, but also thanks to the careful research of the evocative power of images and to the infinite and varied abundance of cultural references.